The Metabolic Fate of ortho-Quinones Derived from Catecholamine Metabolites

Abstract

:1. Introduction

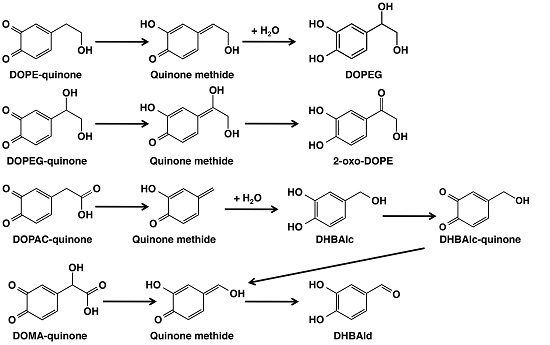

2. Results

2.1. Spectrophotometric Examinations

2.2. HPLC Examinations

| Ortho-Quinone Derived from | Half-Life (t1/2, min) | HPLC Conditions 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| with NaBH4 | with Ascorbic Acid | ||||

| pH 6.8 | pH 5.3 | pH 6.8 | pH 5.3 | ||

| DOPE (1) | 14.6 | 128 | 15.2 | 114 | 80:20, 35 °C |

| DOPEG (2) | 30.9 | 187 | 30.0 | 154 | 90:10, 35 °C |

| DHBAlc (6) from DOPAC (3) | 9.1 | 46.8 | 9.5 | 47.8 | 85:15, 50 °C |

| DHBAld (7) from DOMA (4) | 3.0 2 | 3.3 2 | 3.0 2 | 3.3 2 | 85:15, 50 °C |

3. Discussion

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Materials

4.2. Instruments

4.3. Oxidation of Catecholamine Metabolites with Mushroom Tyrosinase and HPLC Following Oxidation

4.4. Preparation of 2-Oxo-DOPE (5)

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zecca, L.; Bellei, C.; Costi, P.; Albertini, A.; Monzani, E.; Casella, L.; Gallorini, M.; Bergamaschi, L.; Moscatelli, A.; Turro, N.J.; et al. New melanic pigments in the human brain that accumulate in aging and block environmental toxic metals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 17567–17572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Double, K.L.; Ben-Shachar, D.; Youdim, M.B.H.; Zecca, L.; Riederer, P.; Gerlach, M. Influence of neuromelanin on oxidative pathways within the human substantia nigra. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2002, 24, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, D.M.; Yates, P.O. Possible role of neuromelanin in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Mech. Ageing Dev. 1983, 21, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, C.D. Neuromelanin and Parkinson’s disease. J. Neural. Transm. Suppl. 1983, 19, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dias, V.; Junn, E.; Mouradian, M.M. The role of oxidative stress in Parkinson’s disease. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2013, 3, 461–491. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zecca, L.; Stroppolo, A.; Gatti, A.; Tampellini, D.; Toscani, M.; Gallorini, M.; Giaveri, G.; Arosio, P.; Santambrogio, P.; Fariello, R.G.; et al. The role of iron and copper molecules in the neuronal vulnerability of locus coeruleus and substantia nigra during aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 9843–9848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakamatsu, K.; Fujikawa, K.; Zucca, F.A.; Zecca, L.; Ito, S. The structure of neuromelanin as studied by chemical degradative methods. J. Neurochem. 2002, 86, 1015–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakamatsu, K.; Murase, Y.; Zucca, F.A.; Zecca, L.; Ito, S. Biosynthetic pathway to neuromelanin and its aging process. Pigment. Cell Melanoma Res. 2012, 25, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakamatsu, K.; Tanaka, H.; Tabuchi, K.; Ojika, M.; Zucca, F.A.; Zecca, L.; Ito, S. Reduction of the nitro group to amine by hydroiodic acid to synthesize o-aminophenol derivatives as putative degradative markers of neuromelanin. Molecules 2014, 19, 8039–8050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakamatsu, K.; Tabuchi, K.; Ojika, M.; Zucca, F.A.; Zecca, L.; Ito, S. Norephinephrine and its metabolites are involved in the synthesis of neuromelanin derived from the locus coeruleus. J. Neurochem. 2015, 135, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenhofer, G.; Kopin, I.J.; Goldstein, D.S. Catecholamine metabolism: A contemporary view with implications for physiology and medicine. Pharmacol. Rev. 2004, 56, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napolitano, A.; Manini, P.; d’Ischia, M. Oxidation chemistry of catecholamines and neuronal degeneration: An update. Curr. Med. Chem. 2011, 18, 1832–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, S.; Wakamatsu, K. Chemistry of mixed melanogenesis—Pivotal roles of dopaquinone. Photochem. Photobiol. 2008, 84, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zecca, L.; Zucca, F.A.; Wilms, H.; Sulzer, D. Neuromelanin of the substantia nigra: A neuronal black hole with protective and toxic characteristics. Trends Neurosci. 2003, 26, 578–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, S.; Yamashita, T.; Ojika, M.; Wakamatsu, K. Tyrosinase-catalyzed oxidation of rhododendrol produces 2-methylchromane-6,7-dione, the putative ultimate toxic metabolite: Implications for melanocyte toxicity. Pigment. Cell Melanoma Res. 2014, 27, 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, S.; Wakamatsu, K. A convenient screening method to differentiate phenolic skin whitening tyrosinase inhibitors from leukoderma-inducing phenols. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2015, 80, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolton, J.L.; Trush, M.A.; Penning, T.M.; Dryhurst, G.; Monks, T.J. Role of quinones in toxicology. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2000, 13, 135–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, D.G.; Tiffany, S.M.; Bell, W.R., Jr.; Gutknecht, W.F. Autoxidation versus covalent binding of quinones as the mechanism of toxicity of dopamine, 6-hydroxydopamine, and related compounds toward C1300 neuroblastoma cells in vitro. Mol. Pharmacol. 1978, 14, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ito, S.; Okura, M.; Nakanishi, Y.; Ojika, M.; Wakamatsu, K.; Yamashita, T. Tyrosinase-catalyzed metabolism of rhododendrol (RD) in B16 melanoma cells: Production of RD-pheomelanin and covalent binding with thiol proteins. Pigment. Cell Melanoma Res. 2015, 28, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsden, C.A.; Riley, P.A. Tyrosinase: The four oxidation states of the active site and their relevance to enzymatic activation, oxidation and inactivation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014, 22, 2388–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugumaran, M.; Semensi, V.; Saul, S.J. On the oxidation of 3,4-dihydroxyphenyl alcohol and 3,4-dihydroxyphenyl glycol by cuticular enzyme(s) from Sarcophaga bullata. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 1989, 10, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogna, D.; Pezzella, A.; Panzella, L.; Napolitano, A.; d’Ischia, M. Oxidative chemistry of hydroxytyrosol: isolation and characterization of novel methanooxocinobenzodioxinone derivatives. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 8289–8292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lucia, M.; Panzella, L.; Pezzella, A.; Napolitano, A.; d’Ischia, M. Oxidative chemistry of the natural antioxidant hydroxytyrosol: Hydrogen peroxide-dependent hydroxylation and hydroxyquinone/o-quinone coupling pathways. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 1273–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manini, P.; Pezzella, A.; Panzella, L.; Napolitano, A.; d’Ischia, M. New insight into the oxidative chemistry of noradrenaline: Competitive o-quinone cyclisation and chain fission routes leading to an unusual 4-[bis-(1H-5,6-dihydroxyindol-2-yl)methyl]-1,2-dihydroxybenzene derivative. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 4075–4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manini, P.; Panzella, L.; Napolitano, A.; d’Ischia, M. Oxidation chemistry of norepinephrine: Partitioning of the o-quinone between competing cyclization and chain breakdown pathways and their roles in melanin formation. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2007, 20, 1549–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugumaran, M. Tyrosinase catalyzes an unusual oxidative decarboxylation of 3,4-dihydroxymandelate. Biochemistry 1986, 25, 4489–4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugumaran, M.; Dali, H.; Semensi, V. Mechanistic studies on tyrosinase-catalysed oxidative decarboxylation of 3,4-dihydroxymandelic acid. Biochem. J. 1992, 281, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czapla, T.H.; Claeys, M.R.; Morgan, T.D.; Kramer, K.J.; Hopkins, T.L.; Hawley, M.D. Oxidative decarboxylation of 3,4-dihydroxymandelic acid to 3,4-dihydroxybenzaldehyde: Electrochemical and HPLC analysis of the reaction mechanism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1991, 1077, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mefford, I.N.; Kincl, L.; Dykstra, K.H.; Simpson, J.T.; Markey, S.P.; Dietz, S.; Wightman, R.M. Facile oxidative decarboxylation of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid catalyzed by copper and manganese ions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1996, 1290, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugumaran, M.; Semensi, V.; Dali, H.; Nellaiappan, K. Oxidation of 3,4-dihydroxybenzyl alcohol: A sclerotizing precursor for cochroach ootheca. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 1991, 16, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugumara, M.; Dali, H.; Kundzicz, H.; Semensi, V. Unusual, intramolecular cyclization and side chain desaturation of carboxyethyl-o-benzoquinone derivatives. Bioorg. Chem. 1989, 17, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moridani, M.Y.; Scobie, H.; Jamshidzadeh, A.; Salehi, P.; O’Brien, P.J. Caffeic acid, chlorogenic acid, dihydrocaffeic acid metabolism: Glutathione conjugate formation. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2001, 29, 1432–1439. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sugumara, M.; Semensi, V.; Dali, H.; Mitchell, W. Novel transformations of enzymatically generated carboxymethyl-o-benzoquinone to 2,5,6-trihydroxybenzofuran and 3,4-dihydroxymandelic acid. Bioorg. Chem. 1989, 17, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugumaran, M.; Duggaraju, P.; Jayachandran, E.; Kirk, K.L. Formation of a new quinone methide intermediate during the oxidative transformation of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acids: Implication for eumelanin biosynthesis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999, 371, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolton, J.L.; Wu, H.M.; Hu, L.Q. Mechanism of isomerization of 4-propyl-o-quinone to its tautomeric p-quinone methide. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1996, 9, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, D.C.; Thompson, J.A.; Sugumaran, M.; Moldéus, P. Biological and toxicological consequences of quinone methide formation. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1993, 86, 129–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.J.; Nikodinovic, J.; Martin, L.; Doyle, E.M.; O’Sullivan, T.; Guiry, P.J.; Coulombel, L.; Li, Z.; O’Connor, K.E. Production of a chiral alcohol, 1-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)ethanol, by mushroom tyrosinase. Biotechnol. Lett. 2013, 35, 779–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ito, S.; Yamanaka, Y.; Ojika, M.; Wakamatsu, K. The Metabolic Fate of ortho-Quinones Derived from Catecholamine Metabolites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 164. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms17020164

Ito S, Yamanaka Y, Ojika M, Wakamatsu K. The Metabolic Fate of ortho-Quinones Derived from Catecholamine Metabolites. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2016; 17(2):164. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms17020164

Chicago/Turabian StyleIto, Shosuke, Yuta Yamanaka, Makoto Ojika, and Kazumasa Wakamatsu. 2016. "The Metabolic Fate of ortho-Quinones Derived from Catecholamine Metabolites" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 17, no. 2: 164. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms17020164